Welly's parser

This post is about Welly, the programming language I am inventing. Specifically it is about Welly's syntax and parser.

Introduction

My main creative project for the last couple of decades is a new programming language called Welly. It's a work in progress, and a design in flux, though there is an old prototype version you can download and try out.

While I would be delighted if Welly has some users one day, it's not my measure of success. Nor is Welly a money-making project. Instead, Welly is my argument (by demonstration) that programming doesn't need to be as difficult and complicated as it is today. I will consider it a success if future programming languages adopt some of Welly's ideas.

Recently I have been working on Welly's syntax, and its parser. This blog post is a write up of some recent ideas, which have simplified the specification and the implementation. I have made a few changes compared to the prototype, but I don't think I have spoiled the ergonomics of the language. It still feels like a high-level language, designed for humans.

Requirements

In the second half of this post, I will descibe my design decisions and thereby expose myself to your criticism if not ridicule. First, let me criticise some existing languages' syntax decisions, as a way to explain my goals.

Too simple

I'm sure I don't need to explain the motivation for keeping things simple, especially for a low-budget project such as mine. However, even simpler syntaxes do exist, and so I think I do need to explain what I think is wrong with them.

Forth

The syntax of the 1970s programming language Forth is exceptionally simple:

-

Words are separated by whitespace.

-

Some words are numbers. The others can have their meaning defined.

Almost any character is valid as part of a word, but conventionally, only capital letters, digits, and punctuation characters are used.

All the other features that you would expect to be in the syntax of a programming language are pushed into the semantics of Forth's words. For example:

-

Comments: The word

(puts the machine into a state in which it will ignore all words until the next). -

Definitions: The word

:followed by a word puts the machine into a state in which it will compile words into the definition of that word. The word;switches back to the default mode in which words are executed immediately. -

Operator precedence: Forth uses reverse Polish notation, so the formula

3 + 4 * 5would be written3 4 5 * +. The word3(similarly4and5) pushes the number 3 onto a stack, and the word*(similarly+) pops two numbers from the stack, multiplies them, and pushes the result. In summary, the formula has trivial syntactic structure (just a sequence of words), but the run-time stack effect of the words results in structured data flow. -

Variables:

-

Locals: there aren't any (unless your Forth implements the optional Locals word set). Instead, you have to keep values on the stack.

-

Globals:

VARIABLE xreserves a memory location and defines the wordxto push onto the stack the address of that location. The word!pops an address and a value, and stores the value at the addess. The word@pops an address, loads the value at that address, and pushes the result. So something likey = x * 2would be writtenx @ 2 * y !.

-

For illustration, here is an 8-queens solution in Forth (which I paste without having tried to understand it in detail):

variable solutions

variable nodes

: bits ( n -- mask ) 1 swap lshift 1- ;

: lowBit ( mask -- bit ) dup negate and ;

: lowBit- ( mask -- bits ) dup 1- and ;

: next3 ( dl dr f files -- dl dr f dl' dr' f' )

invert >r

2 pick r@ and 2* 1+

2 pick r@ and 2/

2 pick r> and ;

: try ( dl dr f -- )

dup if

1 nodes +!

dup 2over and and

begin ?dup while

dup >r lowBit next3 recurse r> lowBit-

repeat

else 1 solutions +! then

drop 2drop ;

: queens ( n -- )

0 solutions ! 0 nodes !

-1 -1 rot bits try

solutions @ . ." solutions, " nodes @ . ." nodes" ;

8 queens \ 92 solutions, 1965 nodes

Remarkable as this achievement is, I don't like it. The simplicity is illusory, because the syntax can only be understood by first understanding something much more complex, namely the two stacks, the memory model, the dictionary, and the distinction between the interpretation and compilation semantics of words.

The only sense in which the syntax is simple is that it is a tiny increment on something already complex. And the tiny increment looks rather larger when you realise that words in the standard library such as (, :, ;, VARIABLE, ! and @ are needed to express basic concepts for which other languages have syntax.

Perhaps most damningly, there is no part of Forth that understands its own syntax and helps you to use it correctly. If you use it right, it works, but if you don't, then arbitrary nonsense will happen, which will likely be difficult to debug. Writing large Forth programs is difficult and tedious, and this, in practice, limits the purposes for which Forth can be used.

Scheme

The syntax of the 1950s programming language Lisp and its 1970s evolution Scheme is only slightly more complicated than that of Forth:

-

Lists are enclosed in brackets.

-

Strings are enclosed in quotes.

-

There is special syntax for comments.

-

Otherwise, words ("atoms") are separated by whitespace.

-

Some words are numbers. A few are special forms. The others can have their meaning defined.

-

There is special syntax for quoting and unquoting.

There is a minimal set of (for Scheme) 9 "fundamental forms": words with special meanings. These are used to define functions and variables, for conditional code, for quoting, and to define new syntax. There are 14 "derived forms" that can be defined in terms of the fundamental forms, though they are often built in just like the fundamental forms. Together, these 23 "special forms" augment the syntax to the point that it usable by humans for programming.

For illustration, here is an 8-queens solution in Scheme (which again I paste in blissful ignorance):

(import (scheme base)

(scheme write)

(srfi 1))

;; return list of solutions to n-queens problem

(define (n-queens n) ; breadth-first solution

(define (place-initial-row) ; puts a queen on each column of row 0

(list-tabulate n (lambda (col) (list (cons 0 col)))))

(define (place-on-row soln-so-far row)

(define (invalid? col)

(any (lambda (posn)

(or (= col (cdr posn)) ; on same column

(= (abs (- row (car posn))) ; on same diagonal

(abs (- col (cdr posn))))))

soln-so-far))

;

(do ((col 0 (+ 1 col))

(res '() (if (invalid? col)

res

(cons (cons (cons row col) soln-so-far)

res))))

((= col n) res)))

;

(do ((res (place-initial-row)

(apply append

(map (lambda (soln-so-far) (place-on-row soln-so-far row))

res)))

(row 1 (+ 1 row)))

((= row n) res)))

(length (n-queens 8))

I like this more. Special syntax for strings and comments is much easier to understand than special words for them in the standard library, and arguably simpler too. The distinction between the name 'atom and the value of atom is useful. But the real boon is the ability to define nested structures using brackets. Much more human friendly!

A much extolled virtue of Lisp/Scheme syntax is that you can parse it without fully understanding it. If you write a parser that only understands lists, strings and comments (so called "S-expressions"), but knows nothing about numbers, special forms, or quoting and unquoting, then it will generate correct parse trees. In other words, it is a semi-structured syntax. Another well-known semi-structured syntax is XML; there are many different XML file formats, but the same parser works on all of them because it only needs to understand the semi-structure of the file. Lisp benefits from the relative ease of writing and resusing tooling for S-expressions, compared to other syntaxes. Syntax colouring and code formatting is easy, for example. I like this aspect. Welly is also semi-structured.

However, there are still aspects of Lisp/Scheme syntax that I don't like. The special forms are special; making them look just like other words requires the novice programmer to memorise a 23-word list. There is no operator precedence, so the formula 3 + 4 * 5 must be written (+ 3 (* 4 5)). In general, the syntax requires far too many brackets, and tends to make everything look the same when in fact it isn't. And I have so far never been patient enough to understand unquoting, which seems to cause more syntactic problems than it solves.

Too complex

In this section, my victims will be the five languages I most admire: C, Java, OCaml, Python and Rust. The main way in which these languages have become too complicated is by growing over years, in response to their users' requirements, while trying to preserve backwards compatibility. I don't think I need to give examples.

A new language should aim to be simpler than mature languages. The opportunity to remove rather than imitate features of old languages is valuable. This opportunity should not be missed just because the features are familiar. I see unnecessary complexity in mainstream languages that I want to call out. There are some significant sublanguages that deserve to be eliminated.

Literals

In programming languages, literal expressions are the subset of expressions which evaluate to themselves. Examples include true, 5 and "Hello". Examples of structured literals include lists, maps and sets.

We aren't living in the 1970s. Today, all languages have libraries for parsing textual data formats such as JSON, YAML, XML and CSV, and they also have resource files that live in the fast, convenient filing system alongside the source code. So do we really still need syntax for including structured literal data in source code?

We have long ago moved most of the data structures (lists, maps, sets) into libraries, standard or otherwise. This is pragmatic; it removes the complexity of these data structures from the language, where it is expensive to specify and maintain, and adds it instead to libraries, which are explicitly intended for managing this sort of complexity. More specifically:

-

It expresses in the language the complexity of the data structures, which makes it precise and relevant.

-

It allows the data structures to be easily named, versioned, and replaced, like code, and unlike language specifications.

-

It allows the same data structure libraries to be run on different implementations of the language, thereby eliminating some risk of incompatibility.

I think it is time we did the same for data structure literals. Welly therefore won't have literal syntax for list, maps, or sets. Parsers for these data types belong in libraries. This change removes a significant sublanguage. I'm not even sure Welly needs syntax for floating-point numbers; is float("0.5") really that bad?

One popular but bad reason for including structured literal data in source code is so that it can be a compile-time constant. This is at best a partial solution; when somebody publishes a new data structure library, they do not have the opportunity to invent new syntax for its literals. Conversely, it is a false requirement; far too much effort has been spent trying to make specific types of data into compile-time constants, and too little spent wondering if there is a general solution. Welly has a general solution.

Bitwise operators

It is also time to say goodbye to the bitwise operators &, |, ^ and ~. Their main use cases are obsolete, and the remaining uses can be handled using method calls. They do not deserve scarce 1-character abbreviations. Other things do. For example, let's join non-programmers in writing 2ⁿ as 2^n.

Types

Like all good languages, Welly is statically typed. This means that wherever you write an expression, you may or must annotate it with its type. The Welly syntax for annotating a variable name with a type type is name: type. This imitates OCaml, Python and Rust (in contrast to C and Java, which use the syntax type name).

Most languages (OCaml, Rust, C, Java) use different syntax for writing expressions and types. Many (including those four) use a different namespace for naming them. This in turn duplicates the machinery for importing and exporting those names, for defining their scope, and so on. Python is exceptional in this respect: its types are ordinary expressions. I think Python's approach is better.

Python is also exceptional in that there are things that are both values and types. In fact, all Python's types are values, and given any expression expr the expression type(expr) evaluates to its type.

Welly imitates this aspect of Python. Types are ordinary values. They are named, imported and exported in the same namespace as other values. They can also be stored in data structures, computed by functions, and so on, using the full power of the language. This change removes another significant sublanguage (though Welly still has some syntax for type literals).

There are some downsides to this decision. Mainly, Welly cannot use the same syntax to represent both a type and a value of that type, because the distinction cannot be made based on the syntactic context. For example, Welly cannot use the syntax (T, U) for the type of a pair, because that's the syntax for a pair (instead, Welly uses [T, U]). For another example, Welly cannot write the type of a linked list of fruits as LinkedList<Fruit> because LinkedList<Fruit parses as a comparison (instead, Welly uses LinkedList[Fruit]).

Macros

What is true of types is also true of macros. C and Rust each have a significant sublanguage for defining macros, a separate namespace for naming them, and separate mechanisms for importing and exporting them. In contrast, Welly's macros are first-class values, and require no such infrastructure.

Avoiding goto

In 1968 the well-known computer scientist Edsger Dijkstra wrote a two-page article entitled "Go To Statement Considered Harmful" which proved influential. Dijkstra listed a few control-flow structures, including loops and conditional statements, which cover some of the cases where one would otherwise use goto but which avoid its pitfalls.

To these, modern programming languages have added constructs such as break and continue. To help with if statements, languages have added short-circuiting versions of the and and or operators. Interestingly, Dijkstra himself opined that handling exceptions using goto is fine; nonetheless modern programming languages have added throw and catch, or similar constructs. Python's with and Java's finally address the problem of ensuring that something happens on exit from a block of code no matter how that exit is effected. The complexity that has accumulated to fill the gap left by goto is now quite significant.

Though it doesn't fit in this blog post, I have invented a single control-flow construct (match and case) that replaces switch, and, or, break, continue, throw and catch, and which generalises them. In other words it covers all structured uses of goto identified so far, apart from ifs and loops. It meets Dijkstra's criterion for structured programming. This one novel construct removes a significant amount of complexity from Welly's syntax.

Statements

A fragment of a program that can be evaluated to a value is called an "expression". A fragment of a program that can be executed for the effect it has is called a "statement". Contemporary programming languages divide roughly equally into those that disinguish expressions from statements (C, Java, Python) and those that don't (OCaml, Rust). Languages without the distinction can model statements as expressions whose value is some sort of unit, typically the empty tuple ().

In my opinion, which is evidently not universal, languages with statements are better. I could wave my hands about how human language naturally distinguishes nouns from sentences, which I believe is true in some generality. However, I think the best argument is to illustrate the kind of harmful nonsense you can write if you don't make the distinction. In Rust, all of the following are syntactically correct:

return break;

let x = return 1;

if loop { ... } { ... }

println!("Hello {}!\n", continue);

{1; 2; 3; 4; 5}

I concede that there are advantages to control-flow structures that evaluate to a value. For example, C and Java have both if ... { ... } else { ... } (a statement) and ... ? ... : ... (an expression) which intuitively do much the same thing. For another example, I often write in Rust let x = match ...;.

However, I think these cases are better expressed using syntactic adapters from statements to expressions and back. For example, the syntax _ = expr; allows any expression to be used as a statement, and the expression (fn() { ... })() allows any block of statements to be used as an expression (though I would prefer a more ergonomic syntax than the latter).

I have a sneaking suspicion that one of the reasons that expression-only languages persist is that they are easier to implement. It might also be because many are inspired by the lambda calculus, which I would argue is not really suitable for human communication. Even specialists (including me) who have learned to read and write lambda calculus generally regard it as an object of study, not a means of communication. A mathematician will write let f(x) = x² and talk about f, rather than about λx. x². They will not even write let f = λx. x².

A reader correctly points out that an attractive feature of the lambda calculus is its purity: different parts of a program can affect each other only in a controlled way. This freedom from side-effects is in practice shared by remarkably few expression-only languages: not even by OCaml, and I have previously written about making imperative languages pure. I don't see this as an argument in favour of expression-only languages.

REPL

Two of my five admired languages (Python and OCaml) have a shell: an interactive mode where you can type in commands and they will run immediately and show you the results. This is sometimes called a Read-Eval-Print Loop or REPL. I like this. Welly has a REPL.

Perhaps surprisingly, most languages' syntax, and even OCaml's syntax, is not suitable for use in a REPL. The difficulty is in determining when a fragment of a program is large enough to execute. Early interactive languages adopted the idea that a command is ready to be executed when the user presses Enter, but it turns out that limiting commands to one line of input is not ergonomic.

OCaml was forced to invent the abominable ;; notation to mark the end of a command; it's not the end of the world but it is a gotcha that I think every OCaml novice suffers. And of course there is also the burden of explaining why ;; is needed in the REPL but not in OCaml source code files.

In Python (I reverse engineer that) a command is ready to be executed iff (the user presses Enter and) all the brackets have been closed and, if any line outside brackets contains a :, there is a blank line at the end. This heuristic is somewhat ad-hoc and I would guess that it might be post-hoc, i.e. it was invented after the syntax was designed (does anybody know the history?). However it is not too complicated and it works well in practice.

In Welly, a command is ready to be executed iff (the user presses Enter and) all the brackets have been closed, and it ends with } or ;. I hereby record that this is a deliberate decision to facilitate the REPL. I know that some people will think trailing ;s are unergonomic, but they are familiar (from at least C, Java and Rust) and consistent with source code files.

Let me illustrate the differences with some Welly examples which (mutatis mutandis) could also be attempted in Python and OCaml. The three languages do not always behave the same way. OCaml is the most successful language of the three, but at the expense of requiring unergonomic ;; markers. Python often requires a blank line. Welly and Python succeed mostly, and fail on different examples.

// Print the value of `x`.

x;

// Print the value `-5`.

-5;

// Print the value of `x - 5`.

x

-5;

Python fails the third example: it cannot split x - 5 across two lines like this, unless it is enclosed in brackets.

// Do nothing.

if false { print("Hi!"); }

// Error.

else { print("Bye!"); }

// Failure: two separate commands.

if false { print("Hi!"); }

else { print("Bye!"); }

// Print "Bye!".

if false { print("Hi!"); } else { print("Bye!"); }

// Print "Bye!".

if false {

print("Hi!");

} else {

print("Bye!");

}

Welly fails the third example: the "if" statement cannot be split just before the "else". Python requires a blank line after every one of these examples. OCaml requires ;; in addition to the closing bracket.

Welly's syntax

After a number of variously successful experiments, I've ended up with quite a conventional design, with a separate lexer and parser. This gets you to the semi-structured level. Then, a validator checks and disambiguates the parse tree without significantly changing its structure.

Lexer

The lexer recognises the following lexemes:

-

Whitespace is discarded.

-

Comments:

-

Line comments start with

//and extend to the end of the line. -

Block comments start with

/*and end with*/.

These decisions imitate C, Java and Rust.

-

-

String and character literals, including escape sequences:

-

String literals are enclosed in

". -

Character literals are enclosed in

'.

Neither may cross a line boundary. These decisions imitate C, Java, Python and Rust. OCaml literals may cross line boundaries.

-

-

Structural punctuation:

-

;and,are used as separators. -

(,),[,],{and}are used as brackets.

These decisions are universal: the intersection of my five admired languages. Java and Rust additionally use

<and>as brackets, but only in type contexts. Python alone uses structural indentation. OCaml and Rust have additional structural punctuation in the form of arrows. OCaml has several additional kinds of bracket that I can't even remember. -

-

Words made of other punctuation characters:

-

Some such words (including

+,..,<=and%=) are keywords used as arithmetic or assignment operators. -

The rest are illegal.

Note that you cannot juxtapose two such words; whereas in C, Java, Python and Rust you can write

5*-2, in Welly*-would be one word, so you must write5* -2, like in OCaml. -

-

Words made of letters, digits and underscores are atoms. These are further classified:

-

There is a short list (including

and,trueandin) of keywords used in Formulae as arithmetic operators. -

There is a short list (including

if,macroandreturn) of keywords that introduce Items. -

All other alphanumeric words are equivalent in the eyes of the lexer and parser.

-

Parser

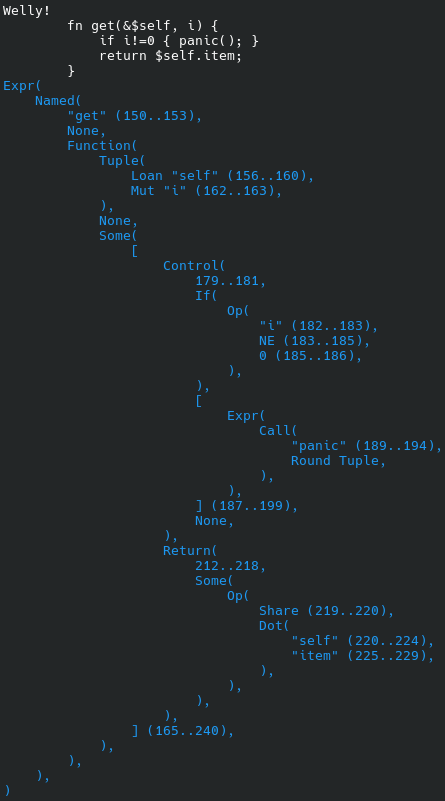

Like that of Lisp/Scheme, Welly's parser operates at a semi-structured level, i.e. it determines the parse tree of the program without fully understanding it. It is quite generous, in the sense that it will guess a plausible parse tree for many syntactically incorrect programs. The validator later enforces more precise syntactic rules.

The parser recognises just four non-terminals:

-

Block - Curly brackets around a sequence of Items

-

Bracket - Round or square brackets around a sequence of Items

-

Item - One of:

-

A separator character

-

A Formula

-

Two Formulae separated by an assignment operator

-

A keyword, then optionally a Formula, then optionally a Block

-

A Block

-

-

Formula - A maximal string of:

-

Alphanumeric words

-

Arithmetic operators

-

Brackets

Note that it is not possible to write two Formulae side-by-side; they will be parsed as a single Formula.

-

Precedence rules

Formulae are futher parsed into operator trees according to the associativity and binding precedence of the arithmetic operators, which are listed in a table. For example, 3 + 4 * 5 parses as (3 + (4 * 5)).

I found it is better to resolve operator binding in the parser, rather than in the validator, because it can report trivial syntax errors such as x + / 1 and x y without waiting for the end of a command.

The precedence pass also disambiguates operators whose meaning depends on whether they are preceded by an value. For example:

-

prefix

-(negation) from infix-(subtraction). -

postfix

( ... )(function call) from nonfix( ... )(a group, or a tuple).

Validator

One of the jobs performed by the validator is to ensure that { ... } always enclose a sequence of Statements, ( ... ) and [ ... ] always enclose a list of Expressions. In both cases, separators are required in some places.

However, the semi-structured syntax talks about Formula and Item, not Expression and Statement. The Expression / Statement structure of Welly programs is non-trivially related to the Formula / Item semi-structure. The rules are as follows:

-

In Blocks:

-

Items must validate as Statements (though any Expressions may be used as a Statement).

-

Items that do not end with a Block must be followed by a semicolon. There must be no other separators.

-

Every Item beginning

elsebecomes part of the previous Item, provided it begins withif,whileorfor, otherwise it is an error. -

An Item that begins with a keyword can, depending on the keyword, require the presence or absence of the following Expression and Block, and can impose further syntactic constraints on them.

-

-

In Brackets:

-

Items must validate as Expressions, not Statements. Items beginning

impl,if,while,for,match,caseorreturnare forbidden. -

Items must be separated by commas, with an optional trailing comma. There must be no other separators.

-

Words

The validator splits alphanumeric words into three categories:

-

Numbers are words beginning with a digit (such as

5and0xAA). It is an error if such a word can't be parsed as an integer. -

Tags are other words of length at least two and containing no lower-case letters (such as

SOME,OKandLESS). These are similar to Lisp's quoted atoms. -

Names are any other alphanumeric word. They can have their meaning defined.

Brackets

The validator splits Brackets into two categories:

-

A Group contains exactly one Expression and does not have a trailing comma.

-

A Tuple is any other Bracket, including an empty one.

These rules follow Python and Rust. OCaml does not allow a trailing comma, so cannot express a 1-tuple, but otherwise uses the same syntax.

On the whole, Welly uses round Brackets to talk about values, and square Brackets to talk about types. For example:

-

OK(result)is a tagged Group of typeOK[Result], ifresultis a value of typeResult. -

(x, y)is a Tuple value of type[Int, Int]if each ofxandyis a value of typeInt.

Named Expressions

If an Item is introduced by a keyword and validates as an Expression, then it can optionally Name the value of the Expression. For example:

-

macro greet(guest) { println("Hello, " + guest + "!"); }defines a macro and Names itgreet. Delete the wordgreetand the Item is still a valid Expression which defines an anonymous macro. -

mod date_time { ... }defines a module and Names itdate_time. Delete the worddate_timeand it defines an anonymous module.

Named Expressions can be generic. For example, the identity function can be written fn identity[T](x: T): T { return x; }.

In these examples, to separate the Name and the generic arguments from any other parameters, the Expression after the keyword obeys a syntactic restriction.

Patterns

Names can also be defined by pattern-matching. The archetype is an assignment Statement. For example, (x, y) = point defines Names x and y. The left-hand side of the assignment is the Pattern, which describes how to unpack the value of the right-hand side and what to Name its pieces. Patterns occur in several other places:

-

the parameter list of a function or macro

-

the field list of an object

-

the parameter list of a

caseStatement.

The syntax of Patterns is a subset of that of Expressions. The validator forbids most arithmetic operators in Patterns; the exceptions are the mode prefix operators $ and &, the type cast infix operator :, and the field access operator .. Call syntax is also forbidden in Patterns, as are several other things.

Selectors

An Expression that is the right operand of . is restricted further still. Currently, only the following cases are allowed:

-

Number -

tuple.0extracts the first field fromtuple. -

Name -

self.xextracts the field namedxfromself. -

Tag -

result.OKchecks thatresultis a value tagged withOK, and evaluates to the value.

for loops

In the Statement for item in sequence { ...; }, the keyword in looks like a structural keyword, imitating Python and Rust. However, the attentive reader will point out that, according to the definition above, Items cannot have such extra keywords.

In fact, the substring item in sequence parses as a Formula: the arithmetic operator in applied to arguments item and sequence. The validator insists that in is the outermost operator, and thereby achieves the effect of a structural keyword without any changes to the parser.

In other contexts the in operator tests membership of a collection. It tests whether its left operand is a member of its right operand. This follows Python. The reuse of in to demarcate for Statements is a pun.

Examples

Here are some illustrative examples:

-

3 + 4 * 5is a Formula that is an Expression that does not define a Name. It can be used as a Statement, but is meaningless except at the top level. -

println("Zounds!")is a Formula which is an Expression. It is also a useful Statement because of its side-effects. -

fn(x: Int): Int { return x + 1; }is an Item that is an Expression; it defines an anonymous function. It can be used as a Statement, but is useless because there is no way to refer to the function. Such an Item would normally only be used as an Expression. -

fn greet(guest: Str) { println("Hello, " + guest + "!"); }is an Item that is an Expression. It defines the Namegreet, making it a useful Statement. -

return books(i).author.phone_numberis an Item which is a Statement but not an Expression.while true { println("I fill your screen!"); }is another example.

Future

I think it is likely that the lexer and parser will not change much from now on. The semi-structured syntax is fit for its purpose. I expect I will change the lists of keywords and arithmetic operators, and I might invent a new kind of literal expression, but nothing more invasive than that. I don't expect to invent any new kinds of Item or Formula, for example, or to invent any new structural punctuation.

The validator is a more fertile place to experiment. I can imagine inventing new kinds of Statement and Expression, and tweaking the subsets of the Expression syntax that are valid Patterns and Selectors. My semi-structured approach makes this sort of change easy and safe; I won't have to rewrite most tools, and there's minimal risk of changing the parse tree of any existing code.

Further information

If you want more details, check out the welly-parser git repo.

As explained in its README.md file, you can type cargo run to try out syntax examples in a sort of REPL. It prints out the parse tree of whatever commands you enter, or reports syntax errors. At the time of writing, this is perhaps the best way to get a feel for Welly syntax.

The git repo contains an examples directory full of longer syntax examples. These are attempts to mock up realistic programming examples in Welly. They might help you to guess what I want the various syntactic constructs to mean.

For the tables of keywords and arithmetic operators, see the source code file enums.rs.

I expect I will be writing a lot more blog posts about Welly, so if you are reading this in the future, make sure to read those too!

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Martin Keegan, Mark Skipper and Reuben Thomas for corrections and suggestions that improved this post.

Last updated 2025/12/19